Chicago’s gay grandaddy of tattooing

How Cliff Raven changed the city’s ink culture forever

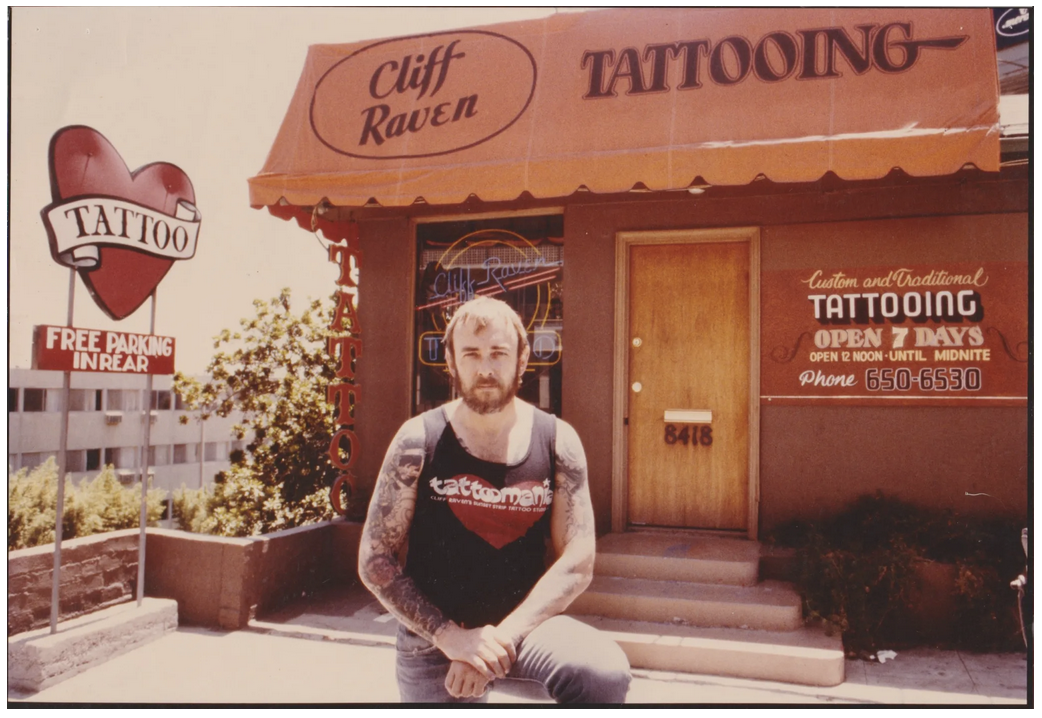

Cliff Raven outside Sunset Strip Tattoo shortly after buying it from Lyle Tuttle

The Chicago Reader 6/24/2020 article by Micco Caporale

“What about Stonewall?” the interviewer asks.

“What about it?” Cliff Raven says.

“Did that have any effect on you when it happened in 1969?” Reading the transcript, you can almost hear Raven taking a drag on a cigarette as he smirks at the question.

“When I really got into tattooing,” he says, “when I became, you might say, successful at it—it was very absorbing of my time. So I wasn’t aware of all the ins and outs and intrigues [of gay politics].”

The conversation is part of an oral history collected for the Leather Archives & Museum by acclaimed leather writer and educator Jack Rinella. It’s between him and one of the most influential tattooers in American history whose success is owed, in large part, to involvement with gay Chicago. If Chuck Renslow was the heart of Chicago’s leather community, Raven was the valve. He shuttled the community’s ideas and influence into a career that elevated the craft and safety of tattooing; but soft-spoken and modest, a man of the “don’t ask, don’t tell” generation, Raven minimized this. By his own account, he was just a very busy tattooer.

Before becoming Cliff Raven, who the Star Tribune once called the “Elvis of Tattooing,” he was Cliff Ingram, a Catholic kid born in 1932 by a steel mill in East Chicago. Early on, he had a mind for details. Some of his favorite childhood memories were leaving Lincoln Park Zoo to walk around with his mother, always a balloon in hand, savoring the features of gilded lamp posts and Victorian two-flats. “Gorgeous,” he’d later write in his diary.

His mother was warm and would invite neighborhood kids over even before Raven was old enough to play, while his father was severe and distant in a way typical of men of that generation. Once, he killed their family dog, Shep, for “showing fear.” That meant Shep was a coward, his father explained, and a coward can’t protect his family. When Raven ran from his first schoolyard fight, his father was quick to label him a coward, too. This would haunt him until the end of his days. Is someone unworthy of love if they’re a coward? Should you just get rid of them?

Perhaps this is some of what drove Raven away from home. There’s not much known about his teens and 20s except that he was wild and wanting. By 15, he had given himself a stick-and-poke of a winged wheel, and at 16, he forged his draft card to get into bathhouses. He started college, then dropped out and fled to New York. But he was strongly connected to his mother, brother, and extended family. In 1957, his mom beckoned him back to the midwest to finish art school at Indiana University, and upon graduation, he settled into a Chicago life in advertising. Over drinks one night, someone mentioned there were bars in New York with “strange” people. Had he heard of these? Men walked around completely decked in leather.

“I perked up,” he explains to Rinella. By this point, Raven was regularly cruising Bughouse Square looking to be picked up by men on motorcycles because he liked tough guys and tough things. “I wasn’t aware of [such bars] when I lived there. I’m not sure if they really were there. I basically said, ‘Oh gee, tell me where they are, so I won’t make the mistake of walking into one!'” Then he planned a New York getaway to find them.

Shortly afterward, he met Renslow and his partner Dom Orejudos, perhaps better known under his art monicker “Etienne” as a pioneer of the buxom gay imagery commonly attributed to Tom of Finland. It was 1959. Renslow and Orejudos were already running Kris Studios, a popular beefcake photography spot, and a gym that kept them amply supplied with sculpted models. Raven brought Renslow some of his erotic drawings, hoping Kris might have a use for them. Instead, he got invited to an orgy. Quickly, something blossomed between Renslow and Raven, and Renslow asked Orejudos if he could bring Raven into their home as a second lover. Not a thruple, he explained, but part of their family. Orejudos gladly accommodated, and “The Family” was born.

Renslow was into BDSM, and Raven became one of his submissives. As Renslow explained to Reader publisher Tracy Baim and Owen Keehnen in The Leatherman: “Our personalities worked well together. He was very passive; that was important. My saying is ‘Boys and dogs should be obedient.'”

Emboldened by his immersion in an erotically charged tough-guy world, Raven felt desperate for a tattoo. Word on the street was this guy Phil Sparrow, then considered Chicago’s most accomplished tattooer, would trade blow jobs for tattoos, so Raven hoped he might trade erotic drawings for ink, too. Sparrow, better known as Samuel Steward, subject of The Secret Historian, gave him a two-inch butterfly on his forearm, and it changed more than his physique.

Sparrow was already friendly with Renslow, and with Cliff’s added interest, each man saw something new in him: for Raven, a career to aspire towards; for Renslow, a potential goldmine. At the time, tattooing was a dangerous line of work, but existing as part of an underworld made it feel like a safe job for a man who wanted to be more openly gay. Plus, for Sparrow, also a BDSM enthusiast, tattooing felt sexual: an exchange of fluids and strong physical sensation, one person desiring pain and handing control to another.

This may be some of what interested Renslow, who learned the basics from Sparrow but quickly lost interest. However, Raven saw tattoos’ artistic potential. Renslow taught what he knew to Raven, and his talents quickly eclipsed his daddy’s. Now working as a freelance commercial artist, Raven took a weekend gig tattooing. It was at a hybrid penny arcade/burger joint two hours south, by Chanute Air Force Base.

Contrary to popular lore, Raven did not assume his surname as a nod to Sparrow or other tattooers with bird monikers. Tattooing was not considered respectable work, and many used pseudonyms to separate their personal and professional lives, especially to spare families any shame or embarrassment their work might cause. Through a queer lens, renaming can be viewed as an act of self determination—a separation from a life on other’s terms vs. a life on one’s own. Raven has never remarked on this. What he has said is, growing up, his father explained “Ingram” meant “Raven” in Old English. If being a tattooer was his most authentic self, he still held his birth family close.

Renslow was an enterprising business person, but everyone in the Family—whose lineage grew and shifted over the years—became part of Renslow Family Enterprises. This helped members share resources, including names for paperwork since homophobic arrests barred some, including Renslow, from legally assuming certain responsibilities. In turn, this grew everyone’s influence and economic stability, including Raven’s.

Raven had the idea to start a leather meetup, and when the group got kicked out of bar after bar, Renslow decided to buy the bar the Gold Coast so they’d have a permanent community site. Ironically, Raven was against this because a financial stake might shift the priorities of the space, but he was outvoted. (Until his death, Renslow insisted Gold Coast was never intentionally or accidentally a moneymaker—always just a gift to his community.) Raven was also a copartner in a short-lived bathhouse and the uncredited art director of Renslow’s bodybuilding magazines Triumph and Mars.

Cliff Raven tattooing in Milwaukee in 1963. When the tattoo age was raised in Chicago, Phil Sparrow started a shop in Milwaukee where he and Raven would tattoo sailors together on the weekends.

In the 60s, tattooing was part of many leather meet-ups, including a large one in New York that also involved legendary piercer, Sailor Sid Diller.

In 1963, amid hepatitis outbreaks, concerns about unsanitary conditions, and nuisances purportedly attracted by tattooing, Illinois raised the tattooing age from 18 to 21. Barely legal military recruits were tattooers’ bread and butter, so Chicago artists either abandoned the trade or moved. According to a 1974 edition of Chicago Guide, the city went from around 20 working artists spread across six shops along State Street to none—except Raven. He loved tattooing too much, and he had a strong community interested in permanent ink. Plus, he’d be the only guy in town.

Under Renslow Family Enterprises, he set up his first solo shop, the Old Town Tattoo Salon, in a storefront of their apartment building on Larrabee Street. When they lost the building to gentrification, they relocated to a rundown spot on Belmont and opened what eventually became Chicago Tattoo Company, which is still in business today. This is when Raven started to feel removed from, as he would say, the “ins and outs and intrigues” of a larger gay scene, but his community was always his life force.

Partially from Sparrow’s encouragement, Raven took to Japanese-influenced tattooing. Nick Colella, owner of Great Lakes Tattoo and unofficial historian of all things Chicago tattoo, believes this was because Japanese tattooing lent itself to intricate, custom, large-scale work. In the 1970s, Raven, Ed Hardy (apprenticed by Sparrow), and Don Nolan were known as “the big three” because they poured over Japanese art and tattooing and fused it with old school Americana to change people’s ideas of what the artform could be. For years, they took all the top prizes at tattoo conventions because of it.

But whereas Hardy was very strict about traditional Japanese imagery and approach, even spending extensive time studying in Japan, and Nolan skewed more Americana, combining the Japanese composite method with a more western visual lexicon, Raven found inspiration to push tattoos’ beauty. Eventually, he abandoned stencils in favor of drawing directly on people’s bodies. His entire working life he traded tips and correspondences with Japan’s most significant tattooers to bring depth and complexity to his work.

“His ability to blend and pack so much color in the skin with the tools they had in the 70s was insane,” Colella says.

In Colella’s private archive, there are photos that register Raven’s pieces as a tribute to the male form: in one, a large Bengal tiger moves along the curve of a man’s thigh to emphasize his buttocks, its tail snaking down the hip, then under and around onto the penis; in another, a garland of flowers are rendered to frame the genitals while accentuating the movement of the man’s breath. It’s work that demonstrates skills honed from deep trust and sensitivity to men’s bodies.

That kind of mindfulness is what put health on the forefront of Raven’s mind. Until the late 60s, tattooers made their own inks and needles. These were highly protected trade secrets that distinguished some artists over others but also made tattooing a little unpredictable and even dangerous. Allergic reactions and infections from ink were common, as was reusing needles and inks because of the time and labor required to make new ones. With the help of then co-owners Buddy McFall and Dale Grande, Raven started Chicago Tattoo Supply, one of the first companies to mass-produce inks and needles. While tattooers had mixed feelings on wider equipment distribution, the growing availability of supplies forced them to confront ways they had been failing clients.

This is also a reason Raven was an early adopter of tattooing with gloves. In 1976, he bought Sunset Strip Tattoos from legendary tattooer Lyle Tuttle and relocated to Los Angeles—a move he’d been dreaming of since childhood, when an aunt on the west coast would send Christmas cards with palm trees. As he explained in his journal, the money and community in Chicago were extremely difficult to give up, but he longed for sunny winters and beaches. Once a Californian, he worked closely with a doctor who provided medical insight to running the cleanest, safest shop possible, which included things like covering surfaces with single-use protective barriers.

When HIV emerged, studios began refusing homosexual customers, and many gay tattooers left the field. In a letter to Raven, one artist explains feeling relief that police raids closed him down. “I do not fancy working continually with people’s BLOOD on my hands in these plague days of anguish and horrible viruses which they . . . don’t know shit about,” he says. His community’s palpable anxiety bolstered Raven’s commitment to providing a medical-grade sterile environment, and it secured him as a beacon to gay men who wanted ink.

Pat Fish, the last tattooer trained by Raven, recalls him saying three things are necessary to be a good tattoo artist: art, craft, and morals. Part of having morals meant prioritizing clients’ health.

“He made me buy an autoclave before he let me buy a tattoo machine,” she laughs. This was in 1985. According to her, gloves weren’t even industry standard until a doctor led a workshop on it at a tattoo convention in 1986—though Greg James, another tattooer who worked with Raven, says they were slowly becoming common in the early 80s. Raven began wearing them in the late 70s, and he was using an autoclave, the machine hospitals use to sterilize reusable equipment, as early as 1970.

At the time he bought Sunset Strip Tattoos, Tuttle laughed and said Raven would be lucky to get by on tattooing alone. Briefly, the space also functioned as a hair salon for his life partner, Pierre Mitchell, who dabbled in tattooing as Bob Raven, Raven’s “brother.” But he grew the shop to support multiple artists, eventually selling it to protege Robert Benedetti in 1985 and retiring to run a used bookstore and private studio with Mitchell in the sleepy city of Twentynine Palms. Thanks to guidance from Raven, networking, and being in the “right place, right time,” Benedetti and James became the premiere tattooers of the Sunset Strip, marking the likes of Ozzy Osbourne, Mötley Crüe, and Guns N’ Roses. Axl Rose can even be seen wearing the shop’s shirt in the video for “Sweet Child of Mine.”

Being gay and having a legacy so robust it’s even visible in music videos has led some to celebrate Raven as an openly queer trailblazer. But this is not exactly accurate. Much of his sexuality is documented because of his proximity to Renslow—they even filmed a BDSM scene together for the Kinsey Institute!—but after leaving the Family, there is scant public information about that part of Raven’s life. By all accounts, those who were meant to know he was gay at the time knew. But everyone else didn’t.

This was as much for Raven’s personal and professional safety as it was a desire for privacy. As Ed Hardy told the Tattoo Archive, Raven was “always a private man.” So much so, many didn’t even know he was deeply spiritual. He abandoned Catholicism in junior high but continued praying and contemplating God till the end of his life. He even kept extensive religious correspondences with his devout Catholic cousin. James describes him as someone who could connect to a high school dropout mechanic as much as an Ivy League-educated lawyer, but Raven was careful how much of himself he revealed and to whom.

In 2001, Raven died of hepatitis C with Mitchell, his lover of 27 years, by his side. In the annals of tattoo history, though, he is immortal.